Types of Lace

There are many different types of lace, even within traditional Irish lace-making. Use the sections below to view some photos of each type of lace, and read some more information about it.

Bobbin Lace

Bobbin Lace, also known as Bone or Pillow Lace – because of the bone used to make bobbins and the hard pillow that supports the work in progress – is the oldest form of lace known in Ireland. Pieces survive that date back more than three hundred and fifty years.

A combination of woven and plaited threads, bobbin lace probably originated in the Mediterranean region, but at what time is still undetermined. Until recently, surviving bobbins gave a date somewhere in the fifteenth century, but an archaeological dig in the eastern Mediterranean has yielded items positively identified by the local lace-makers as bobbins. This find offers a new date as far back as the third century.

From the 1550s onwards there are both pattern books and surviving examples of bobbin lace. Vast quantities of this lace were produced in the Renaissance era and afterwards, and the silver and gold lace of the courts of Europe would always have been produced with bobbins, the thread (linen coated with real silver and gold foil) too intractable for needle techniques.

Bobbin lace was taught in Ireland up to the 1920s but thereafter seems to have disappeared until its revival in Dublin in 1985 by Ann Keller. Ann became interested in making bobbin lace after studying Fine Arts but could not find a teacher in Ireland. She managed to find a teacher in the UK, and later enrolled in the English Lace School in Devon. On her return to Ireland Ann started giving classes in bobbin lace making, later also producing books of original patterns with instructions and developing methods of translating Irish Celtic design into workable Bobbin Lace patterns, which has brought Irish character to the lace and has proved popular. Today Bobbin lace is once again made with enthusiasm by many lace-makers throughout Ireland. Most make it purely as a therapeutic and rewarding hobby, but a few also market their work, mainly motif items such as brooches and pendants, but also collars, handkerchief and clothing trimmings, and wedding and christening lace, and most recently, jewellery, some embellished with crystals, pearls and charms. The new innovations appeal particularly to the young generation.

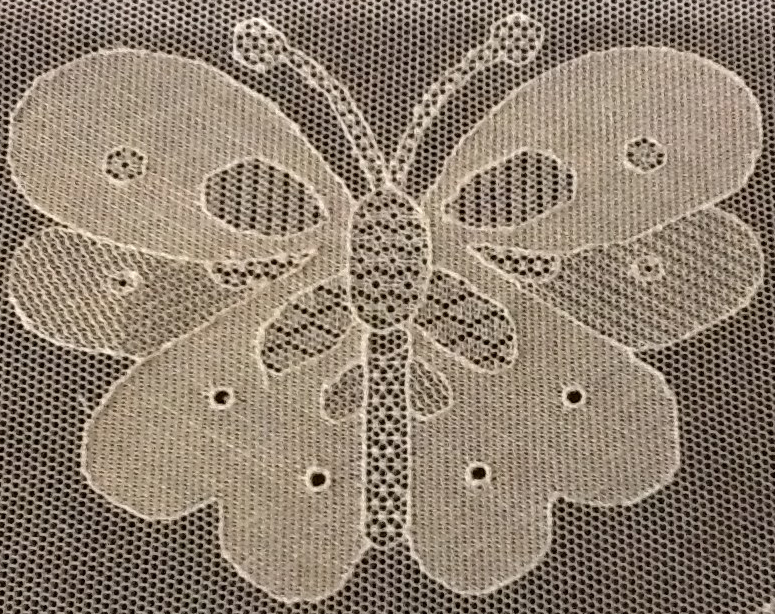

A number of children have joined groups of Young Lace-makers and Bobbin Lace is taught to children from the age of five upwards. The young Lace-makers in particular enjoy experimenting with colour in their work, which is most effectively for jewellery or for pictorial motifs such as butterflies and owls, and Christmas ornaments. However, they also produce good pieces of traditional style using classic patterns and threads, an important factor for the continuation of the quality of traditional lace-maker’s art.

Bobbin Lace is unique among the laces in the decorative appearance of its tools. In most countries the bobbins are plain sticks of wood but Irish lace-makers have followed British traditions and most of the bobbins used in Ireland (sadly there are no known Irish-made antique bobbins in existence) are the English Midland style, spangled with beads and often decoratively painted.

Irish lace-makers take delight in collecting these bobbins, and also the beads which make the spangle at the bottom,( there to weight the bobbin and prevent it rolling during the work). For some the beads themselves have become a special interest, as have the woods and bone used in bobbin making. A small number of wood turners have made bobbins here in Ireland, and being keen to use local woods as much as possible, have used Irish Bog Oak and Bog yew, which make desirable collector’s bobbins when available.

Bobbin lace, perhaps more than any other lace, has brought lace-makers together from far and wide. Always eager to exchange ideas and established patterns, also creates new designs, and to see each other’s bobbin collections. Bobbin lace-makers tend to work in groups rather than alone. This would have been the case in bygone days too as many of the larger patterns were often made in pieces by many lace-makers and then joined together. Nowadays lace-makers are finding these gatherings as valuable from a social and friendship standpoint as for their lace-making.

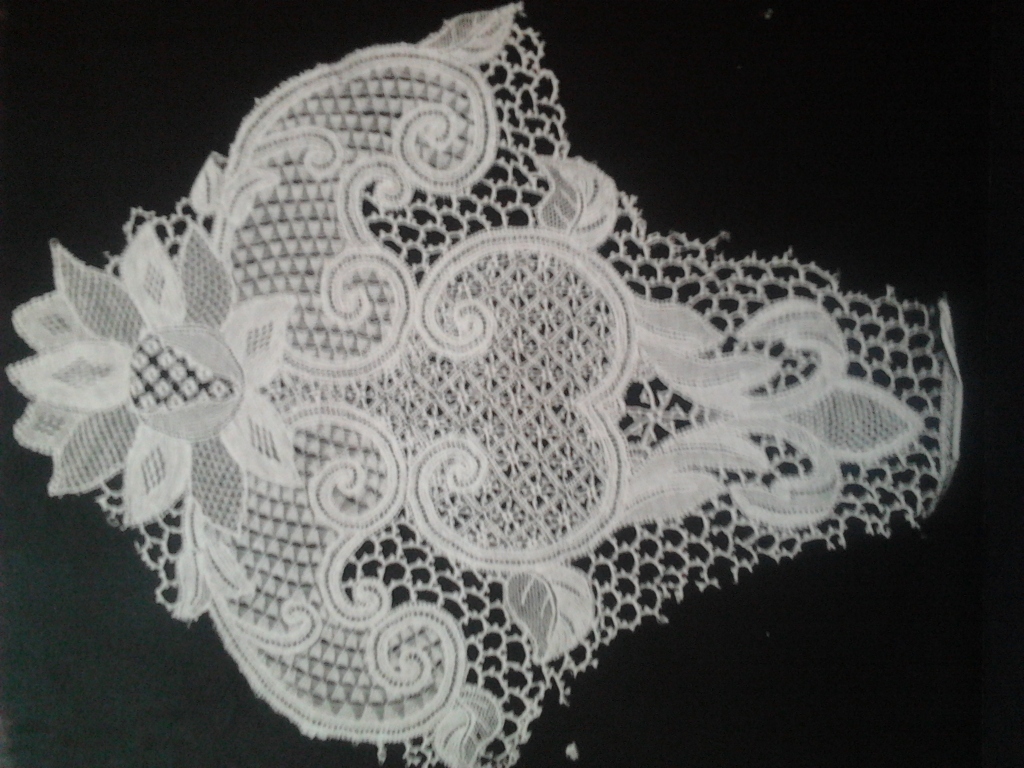

Borris Lace

Borris lace is a tape lace technique similar to Battenberg or Branscombe lace, being made with lace tape joined by various filling stitches. The name of the lace comes from the village of Borris in Co carlow, home of the Kavanagh family. In 1857 Lady Harriet Kavanagh visited Corfu and was so impressed by the specimens of old Greek Lace that she bought some pieces. Lady Harriet, who also bought some specimens of tape laces from Venice and Milan, felt that they could be copied in Borris by the local women, thus enabling them to add to the small earnings of their menfolk.

Lady Harriet was succeeded in her endeavours by her daughter-in-law Frances. Lady Frances Kavanagh expanded the lace-making industry. Classes were held weekly and materials distributed. Lady Frances Kavanagh was also responsible for many of the designs used. World War I saw a decline for Borris lace and by the 1960s there were only three lace-makers left, and most of their work was exported to America, In the early years Borris lace was mainly exported to England, the largest customer being the Irish Linen Stores on New Bond Street, London.

Carrickmacross

Lace-making in Western Europe is generally believed to be of 16th Century Italian origin. It is not surprising therefore that Carrickmacross Lace was first inspired by Italian Applique Lace in the early part of the 19th Century.

In 1816, Rev John Grey Porter, Rector of Donoghmoyne, a parish near Carrickmacross in Co. Monaghan, married Margaret Lindsey who was a descendant of the Earls of Lucan. While on honeymoon in Italy, Mrs. Grey Porter was accompanied by her maid Ann Steadman, who it is reported, was an accomplished needlewoman. Both ladies were fascinated by the Italian Lace they saw and were curious about its construction.

On returning home they decided to copy the Italian Lace. As it happened, they did not copy the Italian Lace but developed and entirely new Lace using linen cambric applied to machine made net to reproduce the effect of lace made with handmade net (reseau). Sometime in the early 1800s Mrs Grey Porter and Ann Steadman began lace classes in the locality. Two variations of the lace evolved – Carrickmacross Applique and Carrickmacross Guipure.

The industry was developed in the neighbourhood of Carrickmacross during the great Famine of 1845-1847. Seven Lace Schools were built on the Bath and Shirley Estates in the years that followed. The lace as popular for its delicacy and charm and the industry flourished. However, towards the end of the 18th century, standards fell and the industry began to decline.

It is possible that lace-making would have died out in the area, were it not for the intervention of the St Louis Sisters, who had founded a convent in the town around 1890. The first ten years of the St Louis School saw a return to prosperity among the lace-makers of the area. Lace-making still flourishes in Carrickmacross and a successful Lace Co-Operative has been established there.

Irish Crochet Lace

The earliest examples of Irish Crochet Lace are believed to date from about 1830 and were made by the students of the Ursuline Convent in Cork.

Mrs. Martha Roberts, wife of the local rector, having unpicked a sample of Venetian Lace proceeded to replicate it in Irish Crochet Lace. In an effort to alleviate the hardships of the Great Famine she started teaching this Irish Crochet Lace at Kilcullen, Co. Kildare in 1846. Soon, her most industrious pupils were producing lace of a very high standard. Those that Mrs. Roberts trained was required to teach another three ,and so on, until hundreds had learned to crochet. At one time there were as many as 700 people, in that area alone, earning a living from crochet. It is estimated that there were as many as 20,000 people earning a living from lace making in Ireland in 1852.

It is interesting to note that one of Mrs. Roberts best workers went to Mrs. Cassandra Hand in Clones Co. Monaghan and from this began the long tradition of lace making in Clones and the surrounding areas. Another of her teachers went to New Ross and was involved with Sr. Columba, of the Convent of Mercy, in the development of the lace school. Others of her teachers went to places around Ireland such as Donegal, Sligo and elsewhere.

The development of lace making owes much to the efforts of the Sisters of the various religious orders such as Nano Nagle, Sr. Columba and many others. Also, the wives of many of the church Rectors were very active in encouraging the teaching of lace-making. The promotion and commercial development was greatly assisted by the patronage of the likes of Lady Aberdeen, Lady Erne, Countess Markiewicz and other prominent ladies of that era. Irish Crochet Lace was much in demand by the fashion houses of Paris and London and was used extensively on elaborate gowns and evening wear in the latter part of the 19th century.

The introduction of cheaper machine-laces and a decline in quality standards led to a decline in sales. Commercial production having ceased by about 1912. Happily the making of Irish Crochet Lace has continued on an individual basis and is actively promoted by the Guild of Irish Lace Makers.

Kenmare Lace

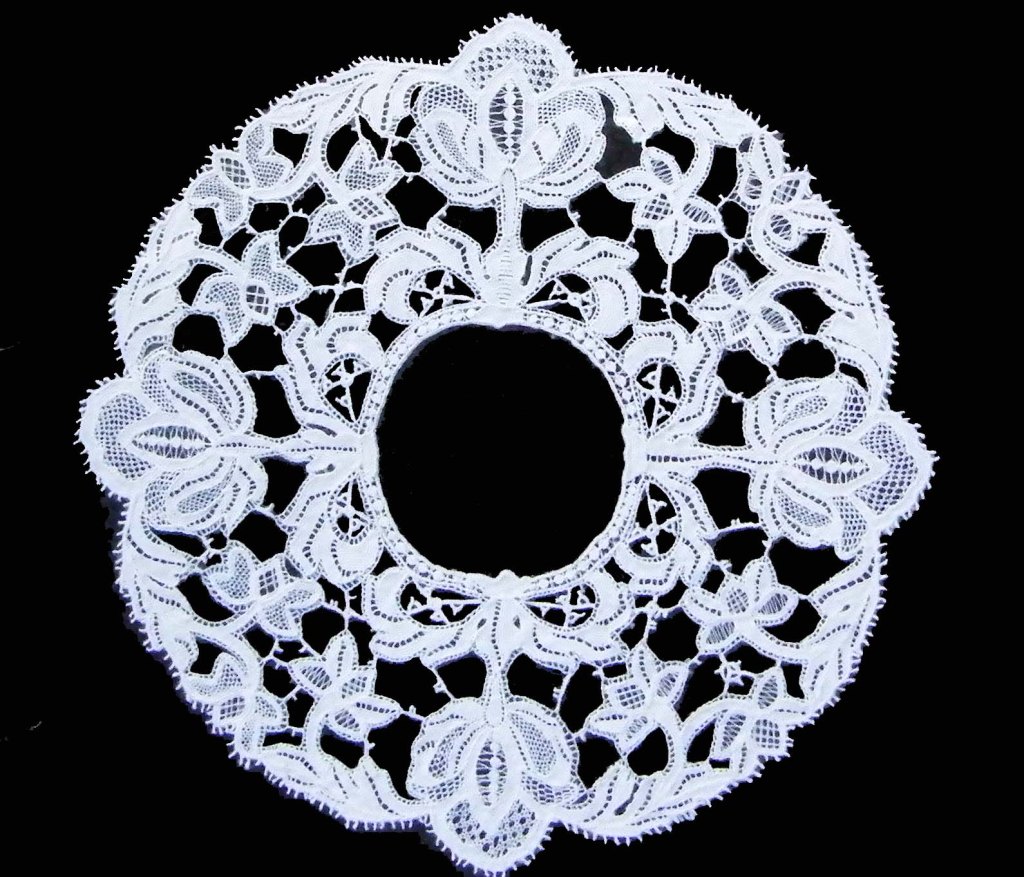

Kenmare Lace is a needlepoint lace and is made with a needle and thread. It is based on the detached buttonhole stitch. Historically linen thread was used in the making of Kenmare Lace. Nowadays however, as it is not possible to get linen thread of sufficient quality, cotton thread is generally used.

The Poor Clares came to Kenmare in 1861.They were requested to come to Kenmare by the Catholic parish priest of the area, Fr. John O’Sullivan to open a school. He believed that this was the best way to help the local people recover

from the rigours of the recent famine. The nuns soon realised that the girls had no way of earning a living once they left the school. They gave them a skill with which to earn a living. That skill was lace-making.

As the girls became more adept they began to produce lace in saleable quantities. Soon tourists began to come to the convent to purchase lace. Later the work was displayed in the local hotel. Some of the nuns had contacts in England and elsewhere who helped find outlets for the work. In a short while many girls began to earn from five to eighteen shillings in a week.

Among the travellers visiting the convent were some well known writers who were so impressed by the work being done in the convent that they helped spread the word.

At the Cork exhibition of 1883 some pieces of lace made in Kenmare, among others, won prizes. Alan Cole who was one of the judges felt that though the work was excellent, design was poor. As a result of this he gave lectures on

design in many of the convents, which were the centres for lace-making around the country.

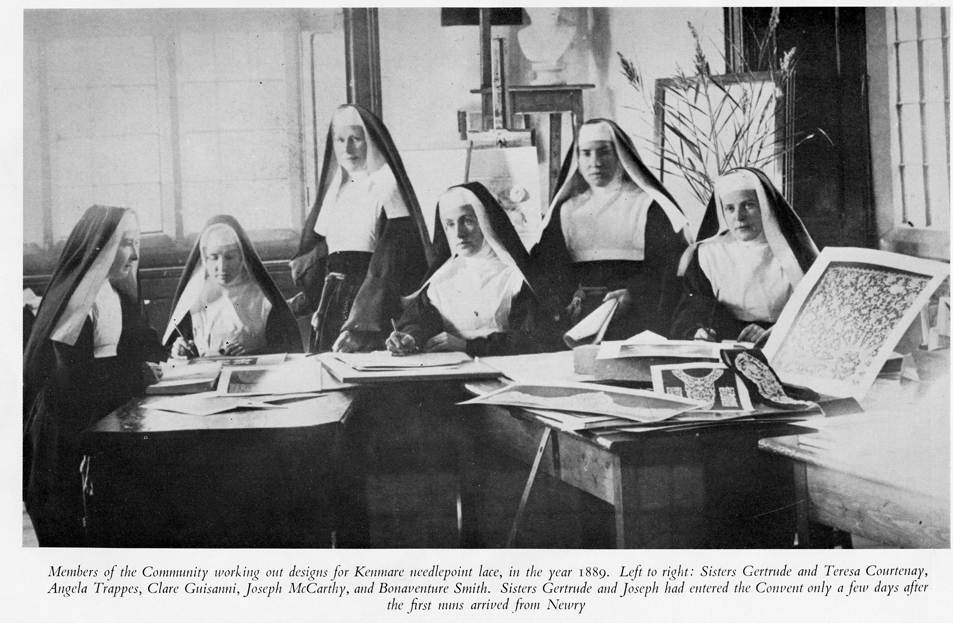

Following this, it was arranged that some of the sisters should study design under competent masters. An art class was established as a branch of the school of Art in Cork under James Brennan R.H.A. The Kensington College of Art allowed the Sisters to have an Examination Centre in their convent so that without infringing their rule of enclosure they might obtain various Art Certificates.”

Kenmare became famous not alone for the quality of their fine needlepoint lace but also for their original designs.

As a result of these classes run by Mr. Brennan two books of lace patterns consisting of over 100 designs plus some others were produced by the nuns.

They were photocopied some years ago. These photocopies are used at the Kenmare Lace and Design Centre by today’s lace-makers while the originals are carefully preserved in the Lace Centre.

This photograph, from the booklet commemorating the centenary celebrations 1861 to 1961, was taken by a Lady Colomb. It is of a group of nuns working on designs. Among them are the sisters Bonaventure Smith, Angela Trappes, Clare Guisanni, Theresa and Gertrude Courtnay and Sr. Joseph McCarthy, daughter of Mr. McCarthy (owner of the Lansdowne Hotel where the lace was displayed).

Limerick Lace

The origin of Limerick lace differs from all other Irish laces in that it was a purely commercial enterprise started by an Englishman, whereas the rest were the outcome of the philanthropy of Irish ladies.

Limerick lace dates back to the late 1880s. Charles Walker, an Englishman married the daughter of a Nottingham lace manufacturer. They moved to Limerick and there founded the lace industry in 1829. They brought over lace workers from England the teach the skills of lace-making to the women of Limerick. By 1842 the industry was well established and hundreds of women were making lace.

After Charles Walker’s death in 1849, some workers returned to England and the lace business declined although some pieces of Limerick lace were shown at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and were awarded medals there. However, the demand for lace fell, and the trade of lace-making in Limerick nearly died. In the 1880s the craft was revived due to the great energy of Mrs Vere O’Brien whose exertions to improve the lace were untiring. She set up a school to teach drawing and design, using her own artistic abilities to revitalize the industry. Under her direction, Limerick lace pieces found their way into the Court of Queen Victoria. At the Convent of the Good Shepherd, the tradition continues to this day.

The beauty of Limerick lace is its delicacy, and the contrast between the outlines of the design and the filling stitches used within small areas called ‘caskets’. In Limerick lace, two methods were used:

(a) Tambour in which the embroidery was done using a hook to work a chain stitch.

(b) Run Lace which is much lighter and more delicate. The design is run on to the net with cotton thread and filled in with darning. Spaces here and there are further ornamented with fancy net stitches.

In old times Tambour and Run Lace were sometimes combined but this fashion did not take.

The amount of work which goes into making Limerick Lace is astounding, but the beauty of the finished article is just reward for such dedicated work.

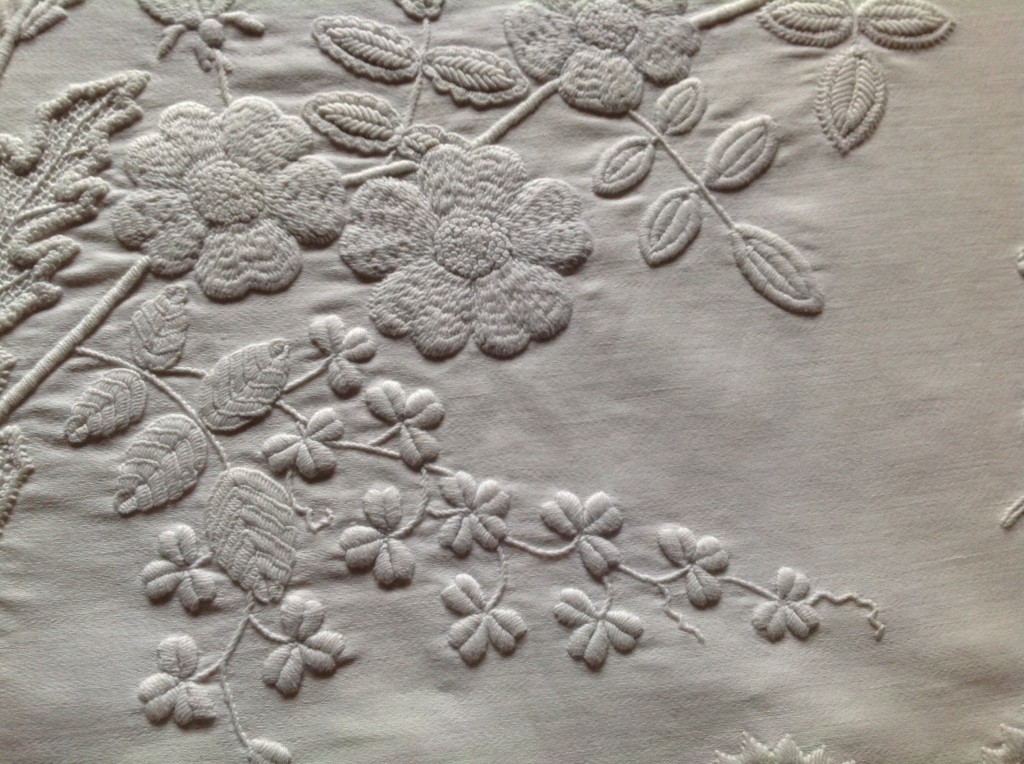

Mountmellick Work

Mountmellick Embroidery takes its name from the Irish Midlands town of Mountmellick, Co Laois where it evolved and was developed in the mid-19th Century. The simple requirements for the embroidery were readily available, these being cotton satin ‘jean’ fabric and matt cotton thread, all in white, and there was a need in the area for female employment. Johanne Carter expanded, literally, the techniques used in the delicate ‘sprigging’ of Ulster and Ayrshire, which in turn were inspired by continental white embroidery. While she apparently had her own workshop in Mountmellick and produced commissioned work, the embroidery style was also taught in the Mountmellick school of the Society of Friends, and thus spread to all parts of Ireland, but particularly the Waterford area.

The characteristics of Mountmellick embroidery are richly worked stitching, often padded, in contrast to the smooth cotton ‘jean’, the whole thing set off by the characteristic knitted fringe. While a total of over forty stitches have been recorded from old pieces, it was most usual to use only ten or so; embroiderers had favourite stitches and executed some better than others, so that the favourite stitch might predominate. As with all other art forms, the success of the finished work was – and is – dependent upon a carefully thought out design, appropriate to the article being worked.

In the 19th century, articles in Mountmellick Work were related primarily to the boudoir – coverlets, pillow-shams, comb and brush bags, and night-dress cases being favourites – and secondly, to the dining room. In Australia, a popular subject was a cloth for the dining-room sideboard, to place under the carving platter and marked ‘Carver’ so that there would be no mistake. Mountmellick Work has enjoyed a renaissance in Ireland in the last few years and uses have expanded to some articles of cloting – christening robes, collars and camisoles – to wedding requirements – kneelers and ring-pillows.

We still have access to the original designs, derived from mainly Irish flora and recently interest has been shown in using original floral design in a more modern way. Today’s practitioners of Mountmellick Work find it most absorbing, giving real scope to needle-workers who are fascinated by stitchery.

Tatting

The art of tatting as we know it has evolved over a long period of time. It can be traced back in its history to Knotting and Macrame, which is acknowledged as the earliest lace. Knotted fringes have been found in the Tombs of Upper Egypt.

The development of Tatting over the centuries is interesting to follow. From Knots developed a running knot that could be pulled into a ring and with a space of thread a series of rings were made. In the 16th century, the Tatting Shuttle was developed which made working much easier. Shuttles were much larger than the ones we know today. This was to accommodate the much thicker threads then in use. Gold thread was used to make Tatted Braid for garments.

The next stage was the arrival of the Picot, which added to the appearance of the lace. However, it was a long time before the Picots were used to join rings and motifs. Prior to this stage the Picots were joined where necessary by needle and thread. The first published article in 1851 on how to join Picots with a crochet hook greatly speeded up the work.. 1864 saw the arrival of the second shuttle or Ball Thread, which was used for working a chain. This was attributed to Eleanore Riego de Branchardiere.

Youghal Lace

Youghal Needle-lace grew out of the need for employment during the potato famine of 1846. A piece of lace of Italian origin came into ownership of Mother Mary Ann Smith of the Presentation Convent, Youghal Co Cork. This piece of lace was unraveled by the nun, who carefully examined how the piece had been executed, and then mastered the stitches. Children in the convent who had shown an aptitude for the needlework were then taught by Mother Smith what she herself had learned. This lace is made entirely by the needle, and the thread used is of very fine cotton.

In 1852 the Convent Lace School was opened. The school flourished achieving many noticeable highpoints. In 1863 a shawl of Youghal lace was presented to the Princess of Wales, (later Queen Alexander) on the occasion of her marriage to the future King Edward VII. This was the first of many presentations to the Royal Family of England.

Several medals were awarded to Youghal Lace in international exhibitions over the years including the Vatican Exhibition in 1888, the Chicago World’s Fair 1893, RDS, and Exhibition of British Lace in London 1906.

After the death of Mother Smith in 1872, work in the Lace Room was carried on by Sister Mary Regis Lynch, who was instrumental in producing many new designs for the lace. The School continued to flourish until the advent of World War I. This effectively did away with many lace markets, although the nuns continued to make lace until the late 1950s.

In 1987, Veronica Stuart from Carrigaline, Co Cork, in conjunction with Sister Mary Coleman, Presentation Convent, Youghal, unraveled a piece of Youghal Lace, just as Mother Mary Ann Smith had done, stitches were learnt and techniques noted. Mrs Stuart traveled to the Continent to perfect her skills in needle-lace and in 1989 she began teaching Youghal Needlelace, happily thus ensuring the survival of yet another old lace.

The Guild of Irish Lacemakers

Proudly powered by WordPress